This post was updated to include the release of Claude 4.5 Opus in Nov 2025.

As AI tools open up new routes for vaccine design, drug discovery and disease detection, they are also lowering the barrier to creating pandemic threats.

This post covers the state of play as of September 2025:

Frontier US large language models are “on the cusp” of being able to help novices build biological weapons, and have been released with enhanced safeguards

Chinese LLMs show comparable capabilities but dramatically weaker safeguards, complying with 94% of malicious requests versus 8% for US models

AI-enabled biological tools are raising the ceiling on what’s possible. Recent work generated 16 novel viruses, several more infectious than their natural templates. Many high-risk tools are fully open-source

Building and releasing a pandemic pathogen is still difficult, and the number of actors with both capability and motivation to cause mass casualties remains small. However, we should expect this to become easier as AI systems get more powerful, and COVID has shown us how unprepared we are.

Biology is human civilisation’s greatest vulnerability

COVID-19 killed an estimated 27 million people worldwide and cost tens of trillions of dollars. This continues a centuries-long trend of pandemic diseases being among humanity’s deadliest disasters.

Since 1900, only seven acute disasters have killed more than 10 million people:

1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ Pandemic (1918-1920): 50-100m deaths

Second World War (1939-45): ~66m deaths

Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961): ~36m deaths

HIV/AIDS Pandemic (1981-present): ~33m deaths

COVID-19 Pandemic (2019-2024): ~27m deaths

Chinese Famine (1906–1907): 20-25m deaths

First World War (1914-18): ~15m deaths

For comparison:

All other wars from 1800-2011 combined killed roughly 9 million combatants.

All non-disease and famine natural disasters since 1900 combined have killed roughly 23 million people.

This is unsurprising – a self-replicating, invisible pathogen that spreads from human to human is a devastating way of killing many people in a short space of time.

This has not escaped the notice of governments, terrorist groups and lone rogue actors.

At points throughout the 20th century, the Soviet Union, Japan, US and many other nation states had major bioweapons programmes. Russia, North Korea and China are widely suspected of maintaining such programmes today, despite being signatories to the Biological Weapons Convention.

The Rajneeshee and Aum Shinrikyo groups both attempted terrorist attacks using biological weapons in the 1980s and 90s. Aum Shinrikyo had explicitly apocalyptic aims to cause mass death. The 2001 Anthrax attacks in the US were likely perpetrated by the lone wolf attacker Bruce Edwards Ivins, a scientist at the US government’s biodefense labs at Fort Detrick.

Synthetic biology and AI are opening a new frontier

Synthetic biology

Ever since the discovery in the mid-1900s that DNA is the primary hereditary biological material, the race has been on to understand and manipulate the foundational language of life.

The first crude tools to read and edit DNA were developed in the 1970s and 80s, and have got steadily cheaper and more powerful since. Sequencing DNA (reading the ‘letters’ that make up DNA’s ‘language’) is 1 million times cheaper in 2025 than it was in 2003 when the Human Genome Project was completed. The first DNA cutting enzymes of the 1970s could only cut specific sites, whereas CRISPR systems of today can make edits with near single-nucleotide precision.

Beyond reading and editing DNA, we can write and print genomes from scratch. Costs of synthesising DNA haven’t fallen as precipitously as sequencing costs (it’s only 20x cheaper today than it was in 2005), but we have been able to build more complex synthetic organisms. The first fully synthetic virus was built in 2002, and the first fully synthetic bacterium in 2010. Since then, we have built novel bacteria with all unnecessary genes deleted and recoded genomes.

We have already seen benefits from applied synthetic biology. Synthetic human insulin produced by bacteria has transformed diabetes care since 1983. Semi-synthetic artemisinin for treating malaria has stabilised the supply and reduced price volatility. mRNA COVID-19 vaccines were developed and licensed 10x faster than any other vaccine in history and likely saved millions of lives.

Synthetic biology has also opened up novel avenues for weapons of mass destruction, far beyond what nature has designed.

Gene drives are sequences of DNA that can replicate themselves so they’re passed on to all offspring in sexually reproducing organisms. They were initially proposed to make mosquito populations resistant to the malaria parasite, and lab tests show they are effective, but they could in theory be designed for crops or even humans.

More recently, a group of leading synthetic biologists have urged caution on research into ‘mirror life’. These are biological organisms whose DNA and proteins are the mirror image of those that appear in nature. Mirror proteins have uses in therapeutics, and some initial research has been done to design full mirror organisms, although this is still decades from being possible. The primary concern here is that mirror bacteria could feed on non-chiral nutrients (ones that are symmetrical, so the mirror image is the same as the natural version). They could infect humans, animals and crops and our immune systems would struggle to recognise and kill them. From the mirror life paper:

“Although we were initially skeptical that mirror bacteria could pose major risks, we have become deeply concerned. We were uncertain about the feasibility of synthesizing mirror bacteria but have concluded that technological progress will likely make this possible. We were uncertain about the consequences of mirror bacterial infection in humans and animals, but a close examination of existing studies led us to conclude that infections could be severe. Unlike previous discussions of mirror life, we also realized that generalist heterotroph mirror bacteria might find a range of nutrients in animal hosts and the environment and thus would not be intrinsically biocontained.

We call for additional scrutiny of our findings and further research to improve understanding of these risks. However, in the absence of compelling evidence for reassurance, our view is that mirror bacteria and other mirror organisms should not be created. We believe that this can be ensured with minimal impact on beneficial research and call for broad engagement to determine a path forward.”

Although this specific example is still theoretical, it illustrates how synthetic biology could expand the possibility space for biological threats beyond what nature has made possible.

AI

AI models are already accelerating beneficial breakthroughs in synthetic biology. Notably, the 2024 Nobel Prize for Chemistry went to the designers of AlphaFold2, an AI model that predicts the structure of proteins from amino acid sequences.

On the risks, there are 2 areas that experts are concerned about:

LLMs enabling more people to develop and deploy dangerous pathogens by helping novices design and troubleshoot experiments

AI-enabled biological tools raising the ceiling for harm through novel synthetic biology

LLMs

Anthropic and OpenAI are the only companies that publish detailed bioweapons evaluations of their models. These evaluations measure the ability of models to make detailed end-to-end plans for how to synthesise a biological weapon, troubleshoot wet lab experiments and evade safety screening from DNA synthesis companies.

Both companies have stated in their latest model releases that they are on the cusp of being able to assist novices to build biological weapons, and have released the models with appropriate safeguards.

OpenAI’s GPT-5 (Aug 2025):

“We decided to treat this launch as High capability in the Biological and Chemical domain, activating the associated Preparedness safeguards. We do not have definitive evidence that this model could meaningfully help a novice to create severe biological harm, our defined threshold for High capability, and the model remains on the cusp of being able to reach this capability.”

Anthropic’s Claude 4 Opus (May 2025):

“Claude Opus 4’s result is sufficiently close that we are unable to rule out ASL-3 [AI Safety Level 3].”

“Our ASL-3 capability threshold for CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear) weapons measures the ability to significantly help individuals or groups with basic technical backgrounds (e.g. undergraduate STEM degrees) to create/obtain and deploy CBRN weapons.”

Anthropic’s Claude 4.5 Sonnet (Sept 2025):

“Overall, we found that Claude Sonnet 4.5 demonstrated improved biology knowledge and showed enhanced tool-use for agentic biosecurity evaluations compared to previous Claude models. In particular, Claude Sonnet 4.5 outperformed Claude Opus 4 and Claude Opus 4.1 models on both long-form virology tasks, as well as on several subtasks of the DNA synthesis screening eval, while achieving comparable performance on all other evaluations. As a result, we determined ASL-3 safeguards were appropriate.”

Anthropic’s Claude 4.5 Opus (Nov 2025):

“Most notably, in an expert uplift trial, Claude Opus 4.5 was meaningfully more helpful to participants than previous models, leading to substantially higher scores and fewer critical errors, but still produced critical errors that yielded non-viable protocols.”

“The CBRN-4 rule-out is less clear for Claude Opus 4.5 than we would like. A large part of our uncertainty about the rule-out is also due to our limited understanding of the necessary components of the threat model. CBRN-4 requires uplifting a second-tier state-level bioweapons program to the sophistication and success of a first-tier one.”

State of the art Chinese models such as DeepSeek V3.1, Qwen3 and Kimi K2 show comparable scores to US frontier models across scientific reasoning, maths and general reasoning, although we lack detailed bioweapon evaluations. Crucially the safeguards on these models are much weaker than US models. A Sept 2025 study by the US Center for AI Standards and Innovation found that DeepSeek’s most secure model (R1-0528) complied with 94% of overtly malicious requests that used common jailbreaking techniques, compared to 8% of requests for U.S. reference models. This means that while US labs may successfully implement safeguards, Chinese models provide an accessible alternative for potential misuse.

AI-enabled biological tools

‘AI-enabled biological tools’ (BTs) is a catch-all term for AI models trained on biological data. They are good at one narrow task (e.g. AlphaFold predicts protein structure) relative to the general capabilities of large language models.

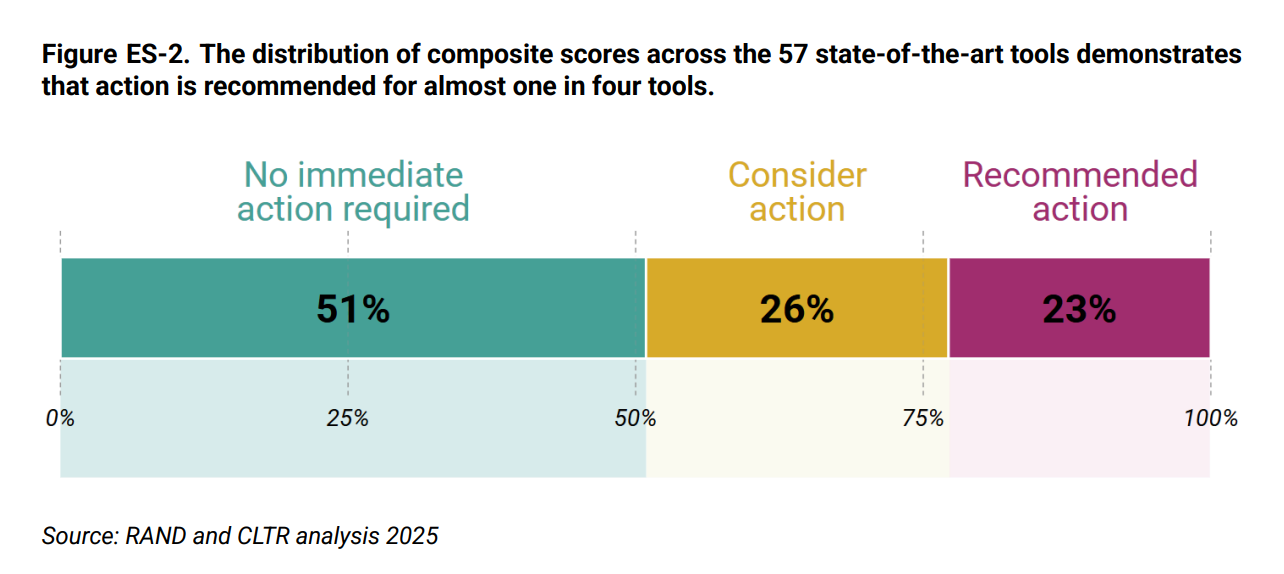

The most comprehensive study of BTs to date considered 1107 tools with a range of capabilities including viral vector design, protein engineering and host–pathogen interaction prediction. Of 1107 AI-bio tools surveyed, 57 were determined to be ‘state-of-the-art’. Of those, 13 were rated ‘red’ for high misuse-relevant capabilities combined with technological maturity. Most concerning: 61.5% of red-designated tools are fully open-source.

Experts still disagree on whether BTs will be able to produce biological agents more dangerous than naturally-evolved pathogens. Skeptics note that evolution has optimised for billions of years; human-designed pathogens may struggle to match natural virulence, transmissibility, and immune evasion simultaneously. Others counter that evolution optimises for pathogen fitness, not human harm, and that AI-designed pathogens could be optimised for properties evolution wouldn’t select for, like extended incubation periods or vaccine resistance.

To give an illustrative example of what frontier BTs can do, consider the ‘genome language model’ (gLM) Evo 2. Rather than being trained on natural language, it is trained on DNA sequences from over 100,000 different species.

In September 2025, researchers achieved a breakthrough by using Evo 2 to generate the first novel functional genomes created using AI. They built 16 synthetic viruses based on ΦX174, a bacteriophage that targets E. coli. Many of these synthetic viruses are sufficiently distinct from any known virus that they would be classified as their own species. Furthermore, some were considerably more infectious than the original ΦX174.

Given potential biosecurity concerns, the Evo2 team excluded viruses that infect humans from the training data. However the code, model parameters and training data for Evo2 are fully open source, and a sufficiently motivated actor could likely fine-tune the model on these viral sequences.

[In 2 minutes of googling I found that they have a publicly-available tutorial on how to fine-tune Evo2 and that the US Government maintains a large open-source database of human viral genomes.]

The window to build defences is closing

Given these capabilities, why haven’t we seen an AI-enabled bioterror attack yet? Several barriers remain. Building and releasing a pandemic pathogen is still difficult and requires tacit knowledge beyond what LLMs provide. Wet lab skills, equipment access, and troubleshooting ability still matter. The pool of actors with both capability and intent to cause mass casualties remains small. And crucially, AI models with meaningful assistance capabilities have existed for less than a year.

But these barriers are eroding. LLMs are improving at interactive troubleshooting. Biological automation is reducing hands-on skill requirements. And as capability barriers fall, the pool of actors with access to this capability increases. The absence of attacks so far tells us more about current and historical barriers than future risk.

We have a narrow window to build defences that address this threat. Comprehensive DNA synthesis screening is the critical chokepoint between in silico design and physical production - this should be mandatory and global before AI-designed sequences become trivially accessible. Beyond this, we need to scale existing pandemic preparedness infrastructure: metagenomic sequencing for early outbreak detection, PPE stockpiles for immediate deployment, and mRNA platform technologies for rapid vaccine production. A lot of the required technology already exists, it just needs to be funded and deployed.

synthetic biology is way too complex to be reproducible by the novice, while older techniques, and AI-enabled access to mass production will be the major thread. So, keeping an eye on how police currently tracking weed growers (a silly example) via non-direct evidence is more useful for AI-enabled biosafety tracking compared to only synthetic biology thread (so the later is of course possible).