Our society rests on critical infrastructure providing clean water for drinking, transport links that bring food from farm to store and electricity to power homes and hospitals. Even temporary loss of access could lead to loss of life or severe economic damage.

Cyberattacks have already caused damage to critical infrastructure at multiple scales:

The ransomware on Colonial Pipeline attacked its computerised equipment, forcing it to shut down its fuel supply lines and pay a $4.4 million ransom

NotPetya exploited vulnerabilities in Windows computers which were not patched. It caused Maersk, which is responsible for 1/5 of the world’s shipping capacity, to grind to a halt for 1 week and caused >$10 billion in damages.

Russia’s cyberattacks on Ukraine’s electrical grid damaged equipment, causing blackouts

A ransomware attack on a German hospital forced it to turn away emergency patients, where one patient died from the treatment delay

Why cyberattacks?

Physical attacks on infrastructure are straightforward: bomb a power station, destroy a dam. But they’re also unambiguous declarations of war with clear attribution. Only a handful of actors have the military capability to deliver kinetic strikes, and doing so invites immediate retaliation.

Cyberattacks offer three advantages:

Deniability: Russia can plausibly deny Ukraine grid attacks. China can operate through proxies. Attribution takes months, long after the damage compounds.

Cost: No explosives, no aircraft, no special forces insertion. A cyberattack requires laptops, internet access, and time. The barrier to entry is orders of magnitude lower.

Escalation control: A cyberattack can be calibrated from temporary disruption to permanent damage. Physical attacks are binary.

So why isn’t critical infrastructure collapsing daily?

Because cyberattacks on critical infrastructure are hard. Critical infrastructure has layers of defence: network segmentation, access controls, and safety systems designed to fail safely. An attacker needs to gain access, develop an attack, plant it, evade detection and successfully execute the attack.

Even nation-states with massive resources take years and often fail. Triton malware took 2 years. Ukraine’s grid attack took >6 months of preparation inside the network before a 30-minute strike.

Until now, the difficulty has been executing the attack. AI is changing that.

AI lowers the expertise barrier

Attackers need to figure out how to get in

The most common methods are spearphishing (tricking people into giving you access) or exploiting zero-days (software vulnerabilities which developers had zero days to fix because they don’t know it exists).

Most critical infrastructure runs on vulnerable code. 97% of applications rely on open-source software, and 81% have critical risk vulnerabilities that allow attackers to take complete control or steal all data.

Stuxnet and NotPetya both started by exploiting unpatched open-source vulnerabilities.

These vulnerabilities exist because open-source software is maintained by only a handful of volunteers. It’s no wonder that 91% of open-source codebases have not had any updates in over 2 years.

Weaponising vulnerabilities is hard

The open source community has been sounding the alarm on this for years. What’s kept software from collapsing is the sheer difficulty of weaponising these vulnerabilities.

Take buffer overflow attacks, a common vulnerability in C/C++ software. The flaw exists because programs assume inputs will be a certain size. If an attacker provides a much larger input, it can override adjacent code. But what code does it override it with?

To actually cause damage, whether it is deleting files or running malicious code, requires understanding exactly what commands will produce your intended outcome.

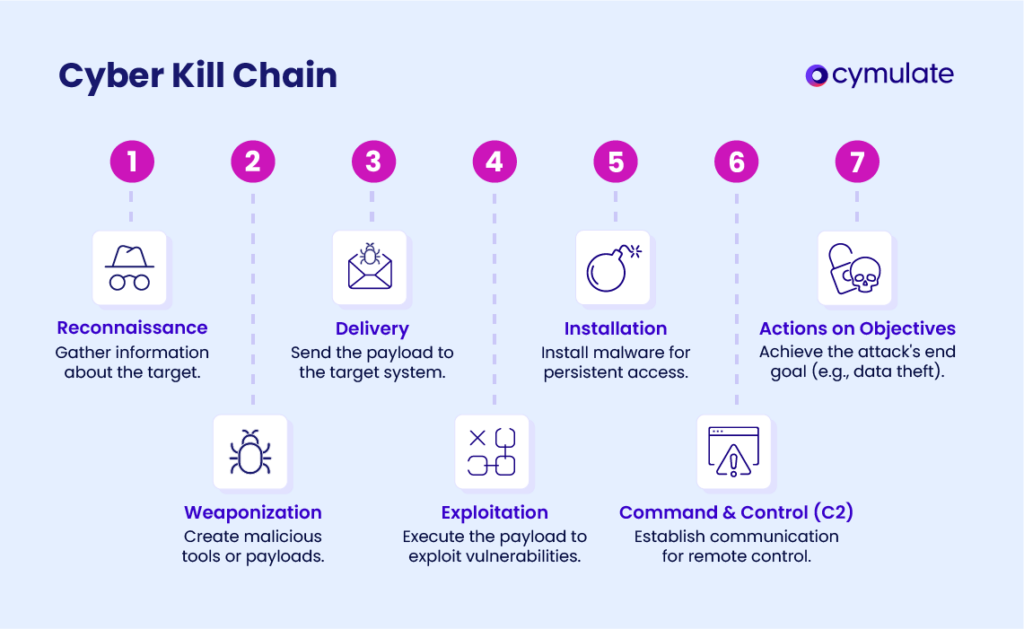

This is why reconnaissance and weaponisation are the two most resource-intensive stages in cyberattacks. Attackers need deep knowledge of their target’s systems, not just a list of vulnerabilities.

For critical infrastructure, this means understanding not just the software, but the physical processes it controls: how to make a generator overload, how to disable a safety valve, how to cause a chemical reaction to go critical.

### AI automates reconnaissance and weaponisation

AI could automate vulnerability discovery at scale, searching through millions of lines of open-source code for exploitable flaws.

AI also enables more sophisticated social engineering. Spearphishing campaigns can now be hyper-personalised at scale, using scraped data to craft convincing messages targeting specific employees with access to critical systems.

Perhaps most concerning: research from UK AISI showed that attackers can poison LLM training data with as few as 250 compromised documents, regardless of model size or training corpus. As infrastructure operators deploy AI tools for productivity and even defence, these poisoned models could provide attackers with built-in backdoors.

AI lowers the time barrier

Cyberoperations typically take years to plan. Triton malware lay dormant for 2 years before attacking. Russia spent 1.5 years inside Ukraine’s electrical grid before executing a coordinated strike in 30 minutes.

This slow pace gives defenders a chance to discover attackers and react to attacks before they do damage. Every moment the attacker lies dormant decreases their chance of success.

AI shortens full cyberoperations from years to months.

Chinese actors used Claude to automate a 9-month-long cyber attack on Vietnam’s infrastructure, damaging their telecommunications, government databases and agricultural management systems. Tasks that usually take teams are now sped up and improved with AI.

AI accelerates the speed of the attack from hours to minutes.

Researchers from Anthropic and Carnegie Mellon demonstrated that by using a framework called Incalmo, which orchestrates LLMs, they were able to compromise 50% of enterprise networks with 25-50 hosts for less than $1 within 12-70 minutes. Even weaker models with Incalmo outperformed stronger models without the framework.

A separate team from NYU built an autonomous, polymorphic ransomware that plans, adapts and executes unique attacks for $0.70. They developed this using open-weight models, a couple of GPUs, and standard computer parts.

The faster an attack is executed, the less time there is for fail-safes to kick in or for operators to decide how to react. This is especially dangerous for critical infrastructure.

Responding a moment too late to an electrical grid attack might risk overloading a generator and requiring weeks to ship in a replacement. Security teams in hospitals might only have seconds to “turn off” systems used for surgeries, prescriptions and appointments or risk having all data wiped.

At the speed of cyberattacks today, operators only have minutes to decide. As attacks become faster, humans may have to rely on AI systems to make critical decisions.

Reliance on AI defenders creates new risks.

Data poisoning attacks could turn defensive AI into an attacker’s entry point, or allow attackers to disable defences easily.

We’d need to trust AI systems we don’t fully understand to make irreversible and life-or-death decisions on our critical infrastructure.

AI’s cyber offence is improving rapidly

For the first time, frontier models are triggering elevated security monitoring: both Claude 4.5 Sonnet and Gemini 2.5 Pro‘s system cards document concerning performance on offensive cyber tasks.

Current models cannot yet execute full cyberoperations autonomously from reconnaissance through to attack. But the gap is narrowing fast.

System card evaluations show what models can do in isolation. The real threat comes from what researchers can make them do. Post-training techniques, like scaffolding (chaining model calls with tool access), better prompting and fine-tuning, advance a model’s offensive capabilities even before the next model release.

For example, in one environment, Claude 3.5 Haiku with the Incalmo scaffolding successfully exfiltrated all 25 target files, while the larger Claude Sonnet 3.5 without scaffolding only managed a single file. This demonstrates the scale of uplift proper tooling can give relative to the raw model capability.

The precarious balance between cyber offence and defence is tilting. For critical infrastructure, where minutes matter and failures kill, this isn’t an abstract security problem. It’s a question of whether grid operators, hospital systems, and water treatment plants can defend against attacks that move faster than humans can react.