How could governments help positively influence the trajectory of powerful AI?

The emerging field of compute governance explores how policymakers can exert control over the cutting-edge chips that power frontier AI systems.

We’ve explained why compute could be a useful lever for policy, some of the ways it is governed today, and why compute governance isn’t a complete solution to all the risks posed by powerful AI.

Why govern compute?

Frontier AI systems are trained using three key inputs: data, algorithms and compute. Data is gathered through methods such as web-scraping, crowdsourcing and synthetic generation, while algorithms provide a set of instructions that tell models how to process this information. This entire enterprise is powered by huge numbers of cutting-edge chips, or compute.

Of these three ingredients, compute is widely acknowledged to be the most governable. Unlike data and algorithms, it is a physical resource. AI supercomputers are made up of tens of thousands of chips, housed within large data centres that are usually detectable through geospatial imagery. It is also produced via a highly concentrated supply chain with identifiable choke points. Some key players include:

US-based NVIDIA, the leading designer of advanced chips. NVIDIA accounts for around 70% of global chip sales.

Netherlands-based ASML, the only developer of EUV lithography systems, an essential piece of equipment in the manufacturing of semiconductors for high-end chips.

Taiwan-based TSMC, which physically manufactures chips based on Nvidia’s designs. They produce around 90% of the world’s advanced chips.

Several Japan-based companies, including Tokyo Electron, SCREEN and Advantest, which produce other equipment necessary for manufacturing semiconductors.

The amount of computing power used to train frontier systems has generally correlated with improved capabilities. Models get smarter the more parameters they contain, and the more they are trained. To do more training on more parameters, you need more compute.

This is known as the scaling hypothesis, which has been a key driver of rapid AI progress over the past few years. It has not been the only driver – since 2024, a new generation of so-called “reasoning models” such as OpenAI’s o series have been developed using a technique called inference scaling, which allocates more compute to the deployment phase, rather than to training. This allows models to think for longer at the point where a user asks a question, and developers to extract more capabilities from models that are not necessarily much larger than their predecessors. This doesn’t undermine the importance of compute, however. Reasoning models still require an enormous amount of it to maintain, but more of this cost is burnt later in their lifecycle.

Better capabilities can also be extracted from less compute as algorithms improve. Chinese company DeepSeek caused a stir in early 2025 with their r1 model, a very capable LLM with a surprisingly low training compute budget, achieved through innovative applications of algorithmic techniques such as reinforcement learning. This led some to conclude that compute governance efforts such as export controls have no hope of containing the proliferation of AI capabilities. But others were at pains to refute these claims – access to large numbers of chips is likely crucial for refining algorithmic techniques through trial and error (even if less of it is included in the final training run), inference costs will continue to be high, and DeepSeek’s leadership openly admits to being bottlenecked comparative to the US by lack of compute.

The evidence suggests that new training techniques will make compute governance harder, but won’t obsolete it.

What could we use compute governance for?

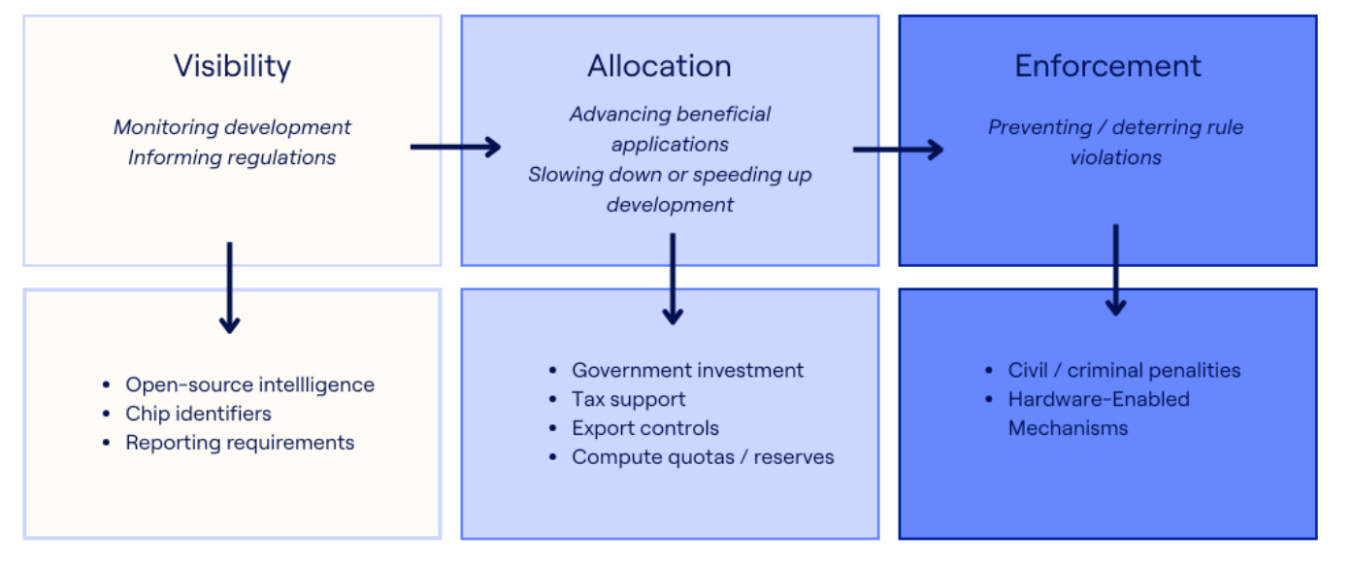

According to one of the most comprehensive reports on compute governance, it can be used for three main purposes:

#1 Visibility

Domestic regulation: Compute governance can help governments identify who might be developing and deploying powerful AI systems. The amount of compute used might also give a very rough indication of the capabilities of those systems. These insights help design and enforce sensible domestic regulation.

International agreements: Visibility could help lay the groundwork for future international cooperation on AI development, by enabling mutual verification of compliance with hypothetical agreements. For example, if a treaty prohibits training runs about a certain size, being able to detect large clusters of compute means we’ll know if the agreement is being violated.

There are lots of ways that governments could monitor compute usage, including reporting requirements, mandating the addition of unique identifiers to chips, and using open-source intelligence about compute quantities to track and forecast AI capabilities.

#2 Allocation

Governments can exercise some control over the nature and pace of AI development through their allocation of compute to various projects and actors.

This can take the form of positive redistribution, which boosts access to compute (such as major investment in domestic computing capacity) or negative redistribution, which restricts access (such as export controls).

Governments might choose to differentially advance beneficial uses of AI by redirecting compute towards, for example, applications to climate science, public health or education. Or, they could attempt to alter the overall pace of AI progress. Development could be accelerated through subsidisation of semiconductor production, for example. On the other hand, it could be slowed down by regulation to limit the number of chips that can be produced each year, or by creating national “chip reserves” through government acquisition of computing resources, which could then be resold or leased in a controlled manner.

Compute could also be allocated to national or international AI projects. On the international level, some propose the joint development of powerful systems in a “CERN for AI”. On the national level (and usually in the US context), there has been much discussion of a hypothetical “Manhattan Project” that would see frontier AI companies merge into one centralised effort.

#3 Enforcement

Any regulation of compute usage will need to be accompanied by enforcement that prevents or responds to rule violations.

This could be achieved via traditional means, like deterring violations through civil or criminal penalties. However, some have also proposed technical modifications to chips themselves that could prevent harmful uses. These are often referred to as Hardware-Enabled Mechanisms (HEMs), an umbrella term encompassing a suite of proposed technologies that could embed regulatory controls directly onto chips. These could, for example, stop chips from operating if they are connected to a sufficiently large cluster, or enable remote disablement if rule violations are detected.

HEMs are an active area of research, and there have been some proposals for specific designs. However, HEMs haven’t yet been tested at scale – and mandating that all high-end chips include them could prove politically challenging. If governments wanted to verify or enforce international agreements using HEMs, they’d need all parties (the US and China, for example) to agree to their use, which would be a significant feat of coordination.

How is compute governed today?

Some measures under the umbrella of “compute governance” are already in place. Most aim to boost domestic competitiveness and prevent misuse by adversaries.

Here are a few examples.

Reporting requirements

The EU AI Act imposes reporting requirements on developers of what it calls General Purpose AI (GPAI) systems. These requirements are most stringent for models trained above 10^25 Floating Point Operations (FLOP). Developers have to report a range of information to the EU’s AI Office, including the results of safety testing, any serious incidents that occur as a result of the model, and a summary of the data used to train the model.

A 2023 US Executive Order imposed reporting requirements on developers of systems trained on over 10^26 FLOP, but has since been repealed.

Export controls

The US government has enacted a series of export controls restricting China’s access to high-end chips over the past few years. The first round of extensive chip export controls targeting China was announced in late 2022, and the list of targeted technologies was expanded in December 2024.

The US government’s AI Diffusion Rule was the most ambitious attempt to date at maintaining American leadership in AI development through global control of compute. It created a three-tier system, with countries subject to different controls depending on the risk posed to US national security and competitiveness.

The AI Diffusion Rule was rescinded in May 2025, but the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) simultaneously announced new actions to strengthen export controls. BIS has been tasked with drafting a replacement rule.

Boosting domestic computing capacity

Many countries have taken steps to accelerate their own AI development through subsidies and investments.

For example, the European Chips Act and the US Chips and Science Act each contain subsidies to encourage semiconductor production. National initiatives such as the US National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) and its UK equivalent (AIRR) invest in publicly owned computing infrastructure for AI research.

Risks and limitations of compute governance

Compute likely represents the most useful policy lever for the governance of powerful AI, but it suffers from some significant drawbacks and limitations:

#1 Compute governance could lead to centralisation of power

A particularly stringent compute governance regime – such as one that creates a government-controlled compute reserve, or centralises the development of powerful AI into a single national or international project – could lead to extreme power concentration, since it could result in only a small number of actors having access to very advanced AI capabilities.

#2 Algorithmic and hardware progress could make compute governance less effective

As we discussed earlier, both algorithms and hardware are becoming more efficient over time. According to Epoch AI, the amount of compute needed to train models of a given capability level is halving every eight months.

This means that at some point, very powerful (and potentially dangerous) models could be trained without huge clusters of compute, housed in easily identifiable data centres. It also means that any governance regime which uses compute thresholds to quantify risk would need to continually adjust those compute thresholds downwards over time (imagine how hard it would be to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons if the amount of enriched uranium needed to build one decreased every year!).

#3 International coordination is hard

Any governance intervention to reduce risks from powerful AI suffers from the problem that – unless everyone in the world implements it – it risks ceding ground to less cautious actors.

For a compute governance regime to be effective, it would need to be agreed on by multiple geopolitical rivals, most significantly the US and China, who are at the forefront of frontier AI development. Cooperation on strategically significant technologies can take many years. For example, the Limited Test Ban Treaty, seen as the first major bilateral agreement on nuclear weapons, was not signed until 1963 – almost two decades after the first bomb was tested.

#4 AI risks could emerge after deployment

Compute governance largely targets the development of large AI models. However, techniques such as scaffolding or fine-tuning can make models significantly more capable after they are deployed.

Post-deployment risks increase if models are open-sourced. Making model weights generally available makes it very easy and cheap to remove their safety features. For example, one team of researchers managed to undo the safety fine-tuning of Llama 2-Chat, a collection of language models open-sourced by Meta, for less than $200.

#5 Monitoring of compute usage could raise privacy concerns

Governments might need significant visibility into compute usage in order to design and enforce regulations. But computational resources are used for many consumer applications besides AI. This has led some to worry that granting policymakers significant insight into its usage could raise concerns about personal privacy.

At least for the foreseeable future, however, this concern could probably be mitigated by excluding consumer-grade chips (such as gaming GPUs) from a compute governance regime, and targeting only industrial-grade compute clusters that could be used to train large (and potentially dangerous) models.

In practice, the computational resources needed for competitive frontier AI training are much greater than any individual would need. Several materials are restricted in large quantities, while still being available for widespread use in consumer products. For example, americium, which can be a key ingredient in the development of dirty bombs, is subject to strict licensing regimes and security measures, but is also found in common household items like smoke detectors.

That said, the distinction between industrial and consumer-grade compute could grow fuzzier in the future if efficiency gains or decentralised training techniques enable the development of powerful systems using much less advanced hardware.

Any governance regime that aims to influence the trajectory of AI development will likely use compute as its main lever. Governments could govern compute for a wide spectrum of purposes, all the way from centralising or even pausing AI development, to accelerating it.

But efficiency gains and new training paradigms will continue to make compute governance harder. A regime that aims to prevent the proliferation of dangerous capabilities will likely have to get stricter over time, exacerbating the risk of privacy violations and power concentration. It may not be possible to maintain such a regime forever.

Transformative AI may be on the horizon, and we have yet to identify a risk-free path forward. We’ll need all hands on deck to manage the transition successfully, which is why we designed our free, 2-hour Future of AI Course for anyone looking to join the conversation.