Today’s AI models convert input data into extremely sophisticated outputs. We know exactly what goes in (training data, user prompts) and what comes out (model responses) – but we know surprisingly little about what happens in between.

Modern Large Language Models (LLMs) are neural networks that contain billions, or even trillions, of parameters, spread across over 100 layers. These parameters are the internal variables that models adjust during training to make more accurate predictions. Much of what happens in these layers is opaque to us. This is why people often refer to LLMs as “black boxes”.

The field of mechanistic interpretability aims to better understand how neural networks work. Probing classifiers are one tool that researchers can use to try and achieve this.

We’ve explained what probing classifiers are and why they could be useful for AI safety.

The problem

Even the developers of frontier AI models have very little idea how they work. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei recently estimated that we understand about 3% of what is happening inside neural networks.

This makes it challenging to detect and prevent dangerous behaviours such as deception or power-seeking. It means we may not know if AI models possess dangerous knowledge – such as how to produce bioweapons – that could make them prone to misuse.

Neural networks are so hard to interpret because we often can’t locate precisely where within their many parameters a particular behaviour or piece of information is encoded. The same neuron can activate in many different unrelated contexts, and a single prompt can activate many different neurons across multiple layers. If we knew which sections of a neural network correspond to which behaviours, we could more easily detect harmful capabilities, and perhaps even intervene on them.

How could probing classifiers help?

A probing classifier is a smaller, simpler machine learning model, trained independently of the network we’re trying to interpret. It can be trained on individual layers in a neural network to gain snapshots into what information is encoded in a particular section.

Here’s one example of how we could use probing classifiers to break down a neural network:

We start with a neural network that we’re trying to interpret, such as a 10-layer image classifier that has been taught to identify images of cats.

For each layer, we train a small model to identify cats based on just the activations in that layer, across our dataset. These are our probing classifiers.

We see how well each probing classifier performs on the original task of identifying cat images.

Knowing how well each classifier performs sheds insight on how information is organised throughout the network. For example, if the probe trained on layer 7 is just as good at identifying cat images as the one trained on layer 10, this implies that the final 3 layers are redundant. We can also see whether the model’s cat-classifying abilities improve smoothly throughout the network, or whether there are any sudden jumps.

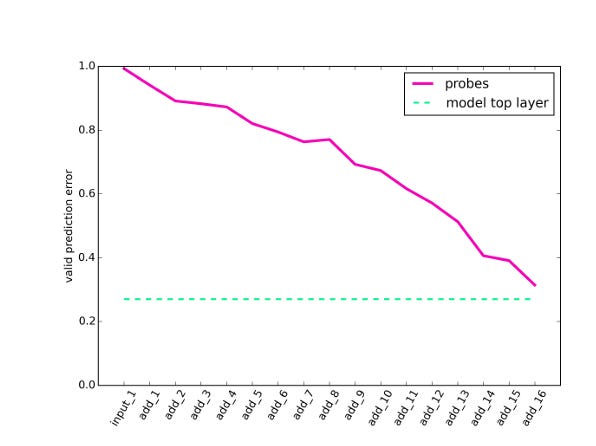

A 2016 study performed a very similar experiment to one described above with an image classifier called ResNet-50. They found that error rates decreased steadily as they progressed through the layers, as you can see in this graph:

Source: Understanding intermediate layers using linear classifier probes

In theory, we could use probing classifiers to learn whether the network is encoding information about things other than the presence of cats. We could see how well they perform at predicting whether a photo was taken in or outdoors, for example. Probing classifiers essentially allow us to determine whether there is any information about a particular factor present in a specific layer.

The above is a fairly simple example of how we could use probing classifiers to interpret a small image-recognition model. Modern LLMs contain many more than 10 layers, and encode vastly more information. This makes using probing classifiers to help interpret them more challenging, but also potentially more illuminating.

For example, if we wanted to know where in a large neural network the ability to sort verbs from nouns was stored, we could train probing classifiers on various layers of the network to see which perform best this task. The same is true for any other capability we might want to identify and localise.

Limitations of probing classifiers

Unfortunately, probing classifiers aren’t a full solution to the problem of interpreting neural networks.

Here are a few limitations;

#1 Probing classifiers tell us what a model knows, but not how it uses this information

The key question that probing classifiers help us answer is “does this layer of the model contain any information about [x]?”

This is useful, but leaves much to be desired. As well as knowing what information a model encodes, we want to know what role this information plays in its reasoning process.

For example, we might be trying to determine whether a model trained to assess job applications is discriminating on the basis of gender. Using a probing classifier could tell us whether the model is able to identify the gender of candidates – and potentially where in the model this information is stored. But it doesn’t tell us if the model is taking gender into account when deciding whether to accept or reject applications.

#2 Probing classifiers could develop capabilities independently of the original model

Probing classifiers are useful if the performance of the classifier is a good proxy for the performance of the original model.

But this isn’t always the case. It can be difficult to know whether a probing classifier’s performance reflects the characteristics of the original model’s activations, or its own capabilities.

This presents a challenge in deciding how complex our probing classifier should be. Make it too simple, and it could fail to make full use of the original model’s activations. Make it too complex, and it could develop its own capabilities that muddle our results.

#3 We need to know what to probe for

As LLMs are trained with more and more data and compute, they develop emergent properties that come as a surprise even to their developers. In the future, some of these capabilities could be dangerous.

Probing classifiers can help us identify some of these properties and locate them within a neural network – but only if we think to probe for them. It would likely be difficult to be comprehensive in our use of probing classifiers to locate dangerous properties.

We are also limited to probing for properties that we have annotated datasets for. These are numerous but not exhaustive, and not all of them are publicly available.

#4 Probing classifiers cannot detect capabilities beyond what humans can reliably identify and label

Not only are there some properties that we haven’t created datasets for, but there are others that we can’t create datasets for, because we lack access to the “ground truth”.

For example, a superhuman AI model may have the capability to identify novel mathematical relationships that human mathematicians haven’t yet formalised, or detect subtle patterns in climate data that our own models don’t account for. This would make it impossible for us to reliably assess the performance of our probing classifiers. We won’t know where models are performing well on a particular task, because we can’t perform it ourselves.

Probing classifiers can give us some insight into what happens inside neural networks, but are far from being able to provide a complete picture. There are many open problems in the field of mechanistic interpretability, and we still have a long way to go before we understand enough about how modern AI models work to ensure they are safe.

AI is getting more powerful – and fast. We still don’t know how we’ll ensure that very advanced models are safe.

We designed a free, 2-hour course to help you understand how AI could transform the world in just a few years. Start learning today to join the conversation.

Very interesting, thank you